Cinthio and Shakespeare

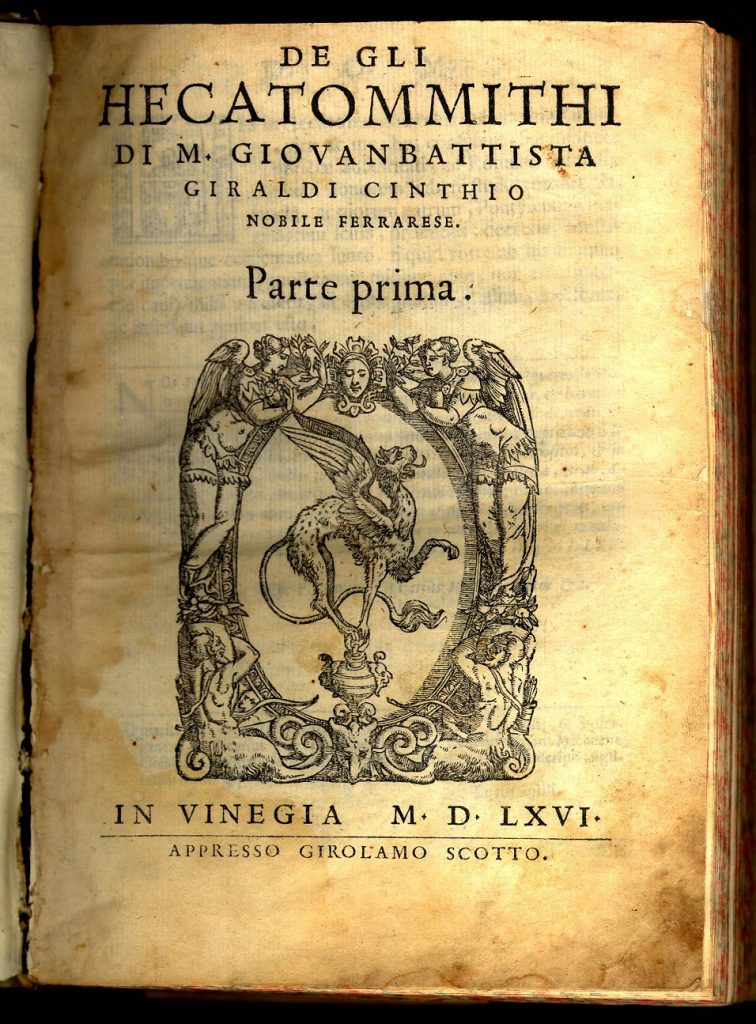

The principal narrative source for the play was the seventh novella in the third decade of Giraldi Cinthio’s Hecatommithi. This collection of tales within a framework, first published in Venice in 1566, was used by a number of Elizabethan and Jacobean dramatists in their search for plots. The fact that it provided the source for Measure for Measure, which was also performed at court at the end of 1604, may suggest that Shakespeare had discovered its professional usefulness about this time. No sixteenth century English translation of Cinthio’s work has survived, although the book was known in England soon after its first publication; and it is difficult to determine with any finality whether Shakespeare used the Italian original or the French translation of Gabriel Chappuys, published in his Premier Volume des Cents Excellentes Nouvelles (1584).

There are four verbal links that draw the play and the Italian version together. Othello’s demand, ‘Give me the ocular proof. ..Make me to see’t’ (3.3.361-5) is closer to Cinthio’s ‘ se non mi fai… vedere co gli occhi ‘ than to Chappuys’s ‘ si tu ne me fais voir’, QI’S use of the unusual word ‘acerbe’ (F ‘bitter’) at 1.3.338 may be an echo of Cinthio’s ‘in acerbissimo odio’; just as Iago’s gloating ‘I do see you’re moved’ (3.3.219) is nearer to the Italian ‘ch’ ogni poco di cosa voi moue ad ira’, where the French verb used is ‘ inciter ‘. Also, the unique Shakespearean usage ‘ molestation ‘, describing the enchafed flood at 2.1.16, may have been influenced by Cinthio’s Moor who speaks of the sea in a similar way in a passage omitted by Chappuys : ‘ ogni pericolo, che ci soprauenisse, mi recherebbe estreme molestia’.

Evidence that it was the French version Shakespeare used is of the same kind. The words ‘if it touch not you, it comes near nobody’ (4.1.187) seem to echo Chappuys’s ‘ce qui vous touche plus qu’à aucun autre’, where the Italian verb is ‘appartiene’; and Iago’s emphasis on the importance of Cassio’s ‘gestures’, as Othello spies on them in 4.1, is nearer to the French ‘gestes’ than the Italian ‘atti’. Perhaps more substantial than these verbal similarities, however, is one of Chappuys’s additions to the original text. In the lines of the play concerning Cassio’s request that Bianca copy the embroidery of the handkerchief, the phrase ‘ take out the work ‘ (or a variant of it) is used three times (3.3.298, 3.4.174, 4.1.145) – a sense of’take out’ found nowhere else in Shakespeare. No similar phrase occurs in Cinthio; but Chappuys adds to the Italian passage dealing with Cassio’s decision the phrase ‘tirer le patron’ (copy the pattern).

In view of the evidence, therefore, one can only say that Shakespeare may have used Cinthio’s original or Chappuys’s translation or both of them, while making due allowance for the possibility of a no longer extant English translation based on them. Cinthio claimed that his tales were taken from real life, and although this is demonstrably not true of some of his stories, the stark realism of his narrative of the Moor and his Venetian wife has sent scholars to Italian history in the search for parallel tragedies of human jealousy. Most of those suggested do have details in common with the play, with one concerning a member of the Moro family, and another featuring a captain nicknamed ‘II Moro’; but none of them strikes one as necessarily having

been in Shakespeare’s mind at the time of the play’s composition.

Of the principal characters in Cinthio’s story only Disdemona is named ; Othello is called simply ‘Capitano Moro’ or ‘Moro’, Cassio is designated as a ‘Capo di Squadra’ (Captain or low-ranking officer), and Iago is an ‘Alfiero’ (Ensign or standard-bearer). The Moor is a distinguished soldier highly valued by the Signory of Venice, and Disdemona falls in love with him for his fine qualities and despite his looks. In defiance of her family’s efforts to make her wed another man, she marries the Moor and they live happily in Venice for some time. When her husband is ordered to take command of the garrison in Cyprus, she pleads eagerly that she may accompany him ; and despite his misgivings about the dangers of the voyage, the Moor allows her to sail with him in his command ship.

In Cyprus, as in Venice, Disdemona’s best friend is the Ensign’s wife, with whom she spends most of her time. The Ensign himself is high in the Moor’s favour, although he is actually a villain with great skill in concealing his true nature beneath a manner that strikes everyone as being soldierly and noble. He passionately desires Disdemona, but is unable to woo her openly because of his fear of the Moor. When she gives no encouragement to his advances, he convinces himself that she is in love with the Captain, who is a great friend of the Moor and a frequent visitor to his house. He tries to formulate a plan by which he may satisfy the hatred he begins to feel for Disdemona in his disappointment; and he decides to accuse her of adultery with the Captain.

A chance to put this plan into action offers itself when the Captain wounds another soldier while on guard-duty and is dismissed by the Moor. Disdemona frequently begs her husband to reinstate the Captain, and the Ensign suggests to his commander that she is so importunate only because she has become disgusted with his looks and his black skin and is sexually attracted to the Captain. The Moor is deeply troubled by the Ensign’s insinuations, and is so violently angry with his wife that she is afraid to persist with her intercession for the Captain.

The Moor demands from the Ensign ocular proof of his wife’s infidelity. So one

day while Disdemona is visiting his wife and playing with his child, the Ensign steals from her girdle an embroidered handkerchief which was her husband’s wedding gift to her, and drops it in the Captain’s bedroom. The Captain, recognizing it as Disdemona’s property, goes to the Moor’s house to return it; but finding the Moor at home and unwilling to risk his displeasure, he runs away. The Moor believes he recognized the Captain in the vicinity of the house and asks the Ensign to find out all he can about the Captain’s relationship with Disdemona.

The Ensign arranges to talk with the Captain while the Moor can observe them

but not hear what they are saying. During the conversation the Ensign acts as though he is amazed at what he is being told, and later tells the Moor that the Captain admitted to adultery with Disdemona and confessed that she had given him her handkerchief the last time they slept together.

When the Moor questions his wife about the loss of the handkerchief, she is so

embarrassed in her behaviour and so confused in her attempts to find it that he takes her reactions to be a proof of her guilt. He becomes obsessed with the idea of killing his wife and the Captain; and he behaves so out of character that Disdemona confides her troubles to the Ensign’s wife, who knows all about her husband’s plans but dare not speak about them because she is afraid of him.

The Captain has in his house a woman very skilled in embroidery who, recognizing the handkerchief as Disdemona’s, decides to copy the pattern before returning it. The Ensign spots the woman at this work sitting in her window, and so brings the Moor to see her that he may be convinced of his wife’s guilt. At the Moor’s request and after having been paid a large sum of money, the Ensign waylays the Captain on his way from a prostitute’s house. However, he botches the murder attempt, succeeding only in cutting off his victim’s leg.

The Moor first considers killing his wife by stabbing or poison ; but finally works out with the Ensign a plan which will enable them to murder her and escape detection. One night while in bed with his wife he orders her to investigate a noise he has heard in the adjoining room. When she does so, the Ensign, who is hiding in a closet, beats her to death with a stocking filled with sand. In order to make the murder appear to be an accident the two men effect the collapse of part of the ceiling on her body.

Soon after Disdemona’s funeral, the Moor, distraught at her loss and repenting of his crime, cashiers the Ensign who thereupon tells the Captain that it was the Moor who attacked him. The Captain duly indicts the Moor before the Signory, who sentence him to be tortured. He persists in denying all knowledge of the crime and is released but banished from Venice. After some time, Disdemona’s family have him murdered in exile. The Ensign later commits another crime for which he is imprisoned; and after his release he dies from the tortures inflicted on him during his incarceration.

Even from this summary it is obvious that Shakespeare took a great deal from Cinthio. The play like the story has two geographical locations: Venice, providing the social and military context in which the characters originate; and the garrisoned island of Cyprus where the principals are isolated and the personal tragedy develops. Cinthio’s conception of the Ensign, with his convincing admirable exterior successfully concealing an enormous native evil, is expanded to become the most credible and frightening of Shakespeare’s villains. The levels of affection between Othello, Desdemona and Cassio grow out of flat statements in the source. It is the Captain’s cashiering that offers the Ensign his chance to sow the seeds of doubt in the Moor’s mind. And in both play and tale it is the handkerchief that provides the crucial ‘evidence’ of adultery which precipitates the tragedy. Everywhere in Cinthio’s narrative also one lights upon small details, words and ideas which are the germs of so many aspects of the play’s totality.

More striking than such similarities, however, are the changes made by Shakespeare as he refashioned the tale. It is noticeable that there is no close following of the source in the first two acts. Rather the emphasis of the original is altered, new characters are created, and mere hints and phrases are developed into speeches and even parts of scenes. A sentence in Cinthio to the effect that Disdemona’s family wished her to marry another man is the seed that produced Desdemona’s noble birth, her elopement, and her distraught and racially prejudiced father – indeed much of the material contained in the first three scenes of the play. The Capo di Squadra, the well-loved visitor to the house of the Moor and Disdemona, becomes Cassio, Othello’s best friend and companion in his wooing, whose promotion to lieutenant alienates the vicious Ensign. This addition to the source in turn gives Iago the professional and personal motivation for his hatred of Othello, which is far stronger than the sexual lust for Disdemona that drives Cinthio’s character.The need for the audience to plumb Iago’s complicated and twisted psyche requires the creation of Roderigo, whose intimacy with the villain enables us to learn much that we may add to the information provided by his soliloquies. Perhaps most remarkable of all are the breathtaking addresses to

the Senate by Othello and Desdemona which Shakespeare conjures out of one bald statement of the Italian original :

It happened that a virtuous Lady of wondrous beauty called Disdemona, impelled not by female appetite but by the Moor’s good qualities, fell in love with him, and he, vanquished by the Lady’s beauty and noble mind, likewise was enamoured of her.

In the later acts of the play Cinthio’s narrative line is followed much more closely; but significant changes are also made here. Iago, with Roderigo’s help, plans Cassio’s disgrace and dismissal specifically to further his plot against Othello. On Iago’s advice Cassio actively solicits Desdemona’s help for his reinstatement. The circumstances surrounding the handkerchief are deliberately changed : Cassio, unlike the Captain, is ignorant of Desdemona’s ownership; Emilia, a waiting-woman rather than the intimate friend of the source, is innocent of any knowledge of her husband’s designs and thus becomes an unwitting provider of the ocular proof. The Captain’s needlewoman and the prostitute he visits are combined in the play to become Bianca, Cassio’s mistress; and the handkerchief itself is made to figure prominently in the overhearing scene. And, of course, the play’s tragic ending is quite different from Cinthio’s sequence of plotted murders, trials, imprisonments and torturings.

No such cataloguing of specific plot and character changes can convey the way in which the sordid story of Italian intrigues became the greatest domestic tragedy in the English language. For it takes no account of the immensely rich poetic texture, the means by which an exotic past impinges on the dramatic immediacy, the relentless emotional grip the play exercises upon the audience in the theatre, and the psychological accuracy with which the characters are conceived and the complexity with which they are imbued. Most of all it does nothing to account for the miracle by which Cinthio’s Moor – ‘ a very gallant man… of great prudence and skillful energy ‘ – becomes Othello, a character who contains such mighty oppositions that he stands second only to Hamlet in his capacity to provoke the widest critical disagreements.

Although Cinthio is the primary source, a number of other influences have been detected. The fourth story of Geoffrey Fenton’s Certain Tragical Discourses (1567), which was translated from Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques (1561), contains in its tale of jealousy and murder details similar to those found in the play and not present in Cinthio. Don Spado, the Othello figure, has a spasm of physical frenzy resulting from his jealous obsession; and his tragedy is set against a background of the Turkish wars. His murder of his wife in their bedroom has a good deal in common with 5.2 of the play – such details as the maid’s calling for help from neighbours who break into the

room; the wife’s revival and attempt to exonerate her husband; the final kiss; and the husband’s suicide across the body of his wronged wife.

In the earlier section of the play it is possible that Shakespeare also drew some details from the second tale of Barnabe Rich’s Farewell to Military Profession (1581), which he had earlier used as a source for Twelfth Night. There are suggestive parallels between Rich and Shakespeare in the handling of such matters as the Christian ruler who must meet the alarming threats from the invading Turks and the storm which separates the defending fleet. But more interesting are the correspondences between Rich’s story and 1.3 of the play, including the Duke’s appointment of a famous military leader, the clandestine courtship of the general appointed, the pursuit of the revenge-bent father, the father’s demand for justice, the senators’ sympathy for the

eloping couple, the summons of the daughter to give her own testimony, and the Duke’s futile attempt to comfort the stricken father.

In building up the character of his noble Moor Shakespeare may also have recalled items from his other reading. There are some interesting similarities between aspects of Othello’s military and personal life and Plutarch’s Life of Cato Utican. In the story of Procris and Cephalus in George Pettie’s A Petite Palace of Pettie his Pleasure (1576)

Shakespeare,William.Othello.Ed.Norman Sanders.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,2003.e-book